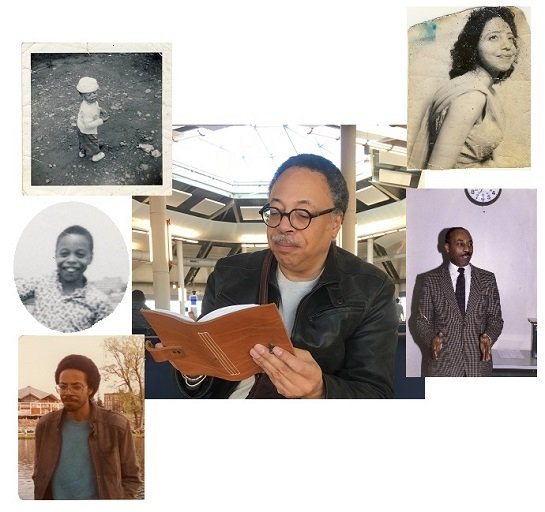

Where Beauty Survived

An Africadian Memoir

by George Elliott Clarke

EXCERPT

I NEED TO SAY MORE about the rainbow of incarnate hues that I encountered as a boy in that magical space of Windsor Plains. My mom, Gerry, looked white (more about that later) as did her mother, born Jean Croxen. Yet, my mom’s sister, my startlingly beautiful and elegant Aunt Joan, is copper-skinned, with wavy black hair. Her first-born son, Scoop, looked white, as did his father. My mom’s youngest brother, my Uncle Sock, looks tan-complected, while her other brother, my Uncle Dave, is closer to beige in complexion.

The reason for this palette of tints among all Africadians is that we intermixed, not only with European Caucasians, but with Indigenous peoples, namely, the Mi’kmaw of Nova Scotia and the American Cherokee who sided with Great Britain, during the War of 1812, and got removed to Nova Scotia, along with Blacks, once they made their way to Royal Navy vessels. Furthermore, because the colonial Government placed Africadians alongside Mi’kmaw reserves (because we were both refuse peoples as far as the Yankee- and -Dixie-descended slaveholders’s Government was concerned), there was lots of exchange, of skills and goods and cultural practices (including drumming and basket-weaving), and, of course, of DNA.

So, my child eyes and mind did not find an automatic discrepancy between the white characters on screens or in schoolbooks and the brown, red, golden, black, and ivory relatives who were all around me and present in any Black community household into which I wandered or chanced to visit. I’ll mention here, too, that my dad, Bill, was mahogany in complexion, while his mother, Nettie, was molasses-coloured, and one of his brothers, Gerald, boasts a creamy buff tint.

✳✳✳

I cannot be too nostalgically Romantic, however. In that other childhood country place that I inhabited, on the outskirts of Halifax, I was shortly reminded that I could think I was “raceless,” but not others. My tutelage in this regard was my introduction to “race”—or, more precisely, racism. That poignant May Day—if May it was—likely fell in 1964. The temperature was genteel, the weather gracious, the sunlight gay. On the small plot of a front yard in front of our house, #117 St. Margaret’s Bay Road, at Halifax, my two brothers, both only slightly younger than me, were playing at—God knows what—maybe burning ants with a magnifying glass or a piece of pop-bottle glass—when our doppelgängers come up the hill—Saint Margaret’s Bay Road—towards our home. (It was two-storey house, fronting on the road, and built on a hillside, so that the lower level had a separate apartment and was somewhat smaller than our upper level. My Uncle Sock stayed there at one point, though I don’t have much memory of his presence.) I’d likely seen them before—these three, older white boys—but I’d paid them little heed, except for according them due respect as schoolboys. They were older. To my child’s mind they were naturally superior to my brothers and me; Bill was still a toddler and Bryant was barely kindergarten age.

I can still see those three boys approaching us—coming up the slight hill toward our home—like wraiths. They were, really, spectres of our future—representatives of the white people who would antagonize us—either directly or indirectly—once we were older and bereft of the protections of childhood myths that Good must always triumph over Evil.

So, as the schoolboys came abreast of us, our home, our driveway, they bent and picked up rocks—pebbles, principally—and fired them at our direction. They yelled, “Niggers,” as they found the stones and threw them at our trio. I don’t think I’d ever heard the word before, though I had a vague sense that it was negative, “an ethnic slur.” However, I’d seen enough Saturday morning Looney Tunes to know that, when attacked, one must defend oneself. I stooped and picked up stones and flung them back, yelling “Niggers” too. My use of “niggers” stunned—perplexed—confused the white boys, for I’m pretty sure their fusillade began to wane as they considered the possibility that they also were “niggers.” Meanwhile, my brothers now joined in the answering fusillade, and a kiddy-level race-riot was on.

While my mother taught at one of the still-segregated schools in North Preston, Nova Scotia, Bill Clarke, who worked nights at the train station, loading and unloading sleeping-car train linens and luggage, either en route to Montreal or just arrived therefrom, was at home. He heard the commotion and strode to the front door of our house and shoo’d the projectile-launching yahoos away. When I turned and saw him, looming dark as a thunder-cloud in our doorway, I sensed that I was in trouble: I knew then that nigger was a “bad” word, and I felt I could be smacked about for the infraction. (I don’t agree with corporal punishment, but my father did.) He called us indoors, and I was nervous, thinking that I would be whipped with a belt for having let a word—that I somehow knew instantly was foul—slip my lips. Being the oldest, I could not escape censure, though—maybe—my brothers could.

However, in a complete reversal of my fears, our father called my brothers and me together and sat us before a mirror. I can still see our three brown faces looking into the unflinching glass. He also un-cupboarded two bowls of sugar—one brown, the other white. He told us to look into the mirror and to take a look at the brown sugar bowl. He explained, “You see that you boys are coloured brown like the brown sugar?” “Yes, daddy,” was our sing-song answer. He then went on to say, “Those boys who were throwing rocks at you were coloured white like the white sugar.” Three heads nodded in unison; three serious, burnt-sienna faces ogled the mirror. Bill Clarke then intoned, “Some white-sugar people don’t like brown-sugar people like us. But don’t use that bad word they use.”

Thus ended his impromptu, schoolmarm-like, storybook-sorta lesson. Did he serve us ice cream afterward—to take the sharp edge off his blunt lesson? Strangely—or not—his favourite dessert was Oreo cookies slathered with vanilla ice cream. He also liked ice cream floats—ginger ale and Neapolitan. I can’t recall such a mollifying gesture. In any event, the stinging, pricking truth of that moment stayed with me—has endured—and rightly so, for the truth of my father’s words—his warning—has coloured my life in every way, from choice of books to read to choice of women to love (and be loved by).

Of course, that Mayday was also confusing: My bitter learning about race arrived with a sweet, sugar-coating.

Was I four years old? If so, my brothers—Bryant and Billy—were two and three years old respectively. But maybe we were all old enough to register what happened. That we were blackened.