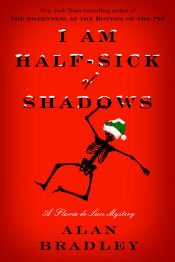

I Am Half-Sick of Shadows

by Alan Bradley

EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER ONE

TENDRILS OF RAW FOG FLOATED up from the ice like agonized spirits departing their bodies. The cold air was a hazy, writhing mist.

Up and down the long gallery I flew, the silver blades of my skates making the sad scraping sound of a butcher’s knife being sharpened energetically on stone. Beneath the icy surface, the intricately patterned parquet of the hardwood floor was still clearly visible—even though its colours were somewhat dulled by diffraction.

Overhead, the twelve dozen candles I had pinched from the butler’s pantry and stuffed into the ancient chandeliers flickered madly in the wind of my swift passage. Round and round the room I went—round and round and up and down. I drew in great lungfuls of the biting air, blowing it out again in little silver trumpets of condensation.

When at last I came skidding to a stop, chips of ice flew up in a breaking wave of tiny coloured diamonds.

It had been easy enough to flood the portrait gallery: an India-rubber garden hose snaked in through an open window from the terrace and left running all night had done the trick—that, and the bitter cold which, for the past fortnight, had held the countryside in its freezing grip.

Since nobody ever came to the unheated east wing of Buckshaw anyway, no one would notice my improvised skating rink—not, at least, until springtime, when it melted. No one, perhaps, but my oil-painted ancestors, row upon row of them, who were at this moment glaring sourly down at me from their heavy frames in icy disapproval of what I had done.

I blew them a loud, echoing raspberry tart and pushed off again into the chill mist, now doubled over at the waist like a speed-skater, my right arm digging at the air, my pigtails flying, my left hand tucked behind my back as casually as if I were out for a Sunday stroll in the country.

How lovely it would be, I thought, if some fashionable photographer such as Cecil Beaton should happen by with his camera to immortalize the moment.

‘Carry on just as you were, dear girl,’ he would say. ‘Pretend I’m not here,’ and I would fly again like the wind round the vastness of the ancient panelled portrait gallery, my passage frozen now and again by the pop of a discreet flash bulb.

Then, in a week or two, there I would be, in the pages of Country Life or The Illustrated London News, caught in mid-stride—frozen forever in a determined and forward-looking slouch.

‘Dazzling … delightful … De Luce’, the caption would read. ‘Eleven-year-old skater is poetry in motion.’

‘Good lord!’ Father would exclaim. ‘It’s Flavia!

‘Ophelia! Daphne!’ he would call, flapping the page in the air like a paper flag, then glancing at it again, just to be sure. ‘Come quickly. It’s Flavia—your sister.’

At the thought of my sisters I let out a groan. Until then I hadn’t much been bothered by the cold, but now it gripped me with the sudden force of an Atlantic gale: the bitter, biting, paralysing cold of a winter convoy—the cold of the grave.

I shivered from shoulders to toes and opened my eyes.

The hands of my brass alarm clock stood at a quarter past six.

Swinging my legs out of bed, I fished for my slippers with my toes, then bundling myself in my bedding—sheets, quilt and all—heaved out of bed and, hunched over like a colossal cockroach, waddled towards the windows.

It was still dark outside, of course. At this time of year the sun wouldn’t be up for another two hours.

The bedrooms at Buckshaw were as vast as parade squares—cold, draughty spaces with distant walls and shadowy perimeters, and of them all, mine, in the far south corner of the east wing, was the most distant and the most desolate.

Because of a long and rancorous dispute between two of my ancestors, Antony and William de Luce, about the sportsmanship of certain military tactics during the Crimean War, they had divided Buckshaw into two camps by means of a black line painted across the middle of the foyer: a line which each of them had forbidden the other to cross. And so, for various reasons—some quite boring, others downright bizarre—at the time when other parts of the house were being renovated during the reign of King George the Fifth, the east wing had been left largely unheated and wholly abandoned.

The superb chemical laboratory built for my great-uncle Tarquin, or ‘Tar’ de Luce by his father, had stood forgotten and neglected until I had discovered its treasures and made it my own. With the help of Uncle Tar’s meticulously detailed notebooks and a savage passion for chemistry that must have been born in my blood, I had managed to become quite good at rearranging what I liked to think of as the building blocks of the universe.